Why am I so Gassy?

- Adam Rinde, ND

- Dec 23, 2022

- 6 min read

Updated: Jun 4, 2023

Feeling bloated, burpy, and/or flatulent is a normal transient experience for most. However when persistent for days or weeks it can be alarming and concerning for someone who has no explanation for these symptoms.

updated 6.4.2023

It's important to first recognize that having intestinal gas is normal and we wouldn't be alive if we didn't have it. It's also important to realize the humans produce a tremendous amount of gas and other organic compounds.

In the body, gas producing Volatile Oil Compounds (VOC's) are produced by inflammation/oxidative stress during physiological and pathological metabolic processes. Also in the body, VOCs can also originate from exogenous sources such as foods, drugs, and microbes. They are excreted and detected via urine, skin, blood, feces and exhaled breath.

Over 1000 VOC's can be detected in the breath. In certain conditions like IBS, IBD, and SIBO volatile oil production can be dysfunctional.

Right now only three gases are being detected in clinical settings for use with diagnostic gas related problems and those are Breath Hydrogen Sulfide, Breath Methane, and Breath Hydrogen.

However ,there is a whole field of study called Volatomics which is looking at the over 1000 VOC's produced by humans and the association these gases have with various disease states.

For example in studies, only one compound (1-methyl-4-propan-2-cyclohexa-1,4- diene) was increased in fecal and breath samples comparing IBS patients to Healthy Volunteers.

For Crohn's Disease Propan-1-ol was increased in feces and breath in four studies comparing chron's disease patients to healthy volunteers.

Volatomics biomarkers being detected in the research depicting VOC's that are more present in active vs. remission disease states in CD and UC. As well as VOC's in CD compared to healthy populations. And IBS vs Healthy volunteers.

from: Van Malderen K, De Winter BY, De Man JG, De Schepper HU, Lamote K. Volatomics in inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. EBioMedicine. 2020 Apr;54:102725. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102725. Epub 2020 Apr 21. PMID: 32330874; PMCID: PMC7177032.

The majority of gas in our intestine is Nitrogen (N2) . And the rest is made up of oxygen (O2), carbon dioxide (CO2), hydrogen (H2), and methane (CH4), and hydrogen sulfide (H2S).

We normally have 200 ml of Intestinal Gas passing through our intestines.

Oxygen is usually the lowest represented gas and Nitrogen is the highest.

The stomach has predominantly odorless gas of Nitrogen and Oxygen. Whereas the colonic gas contains predominantly the odorless gas of Methane and O2.

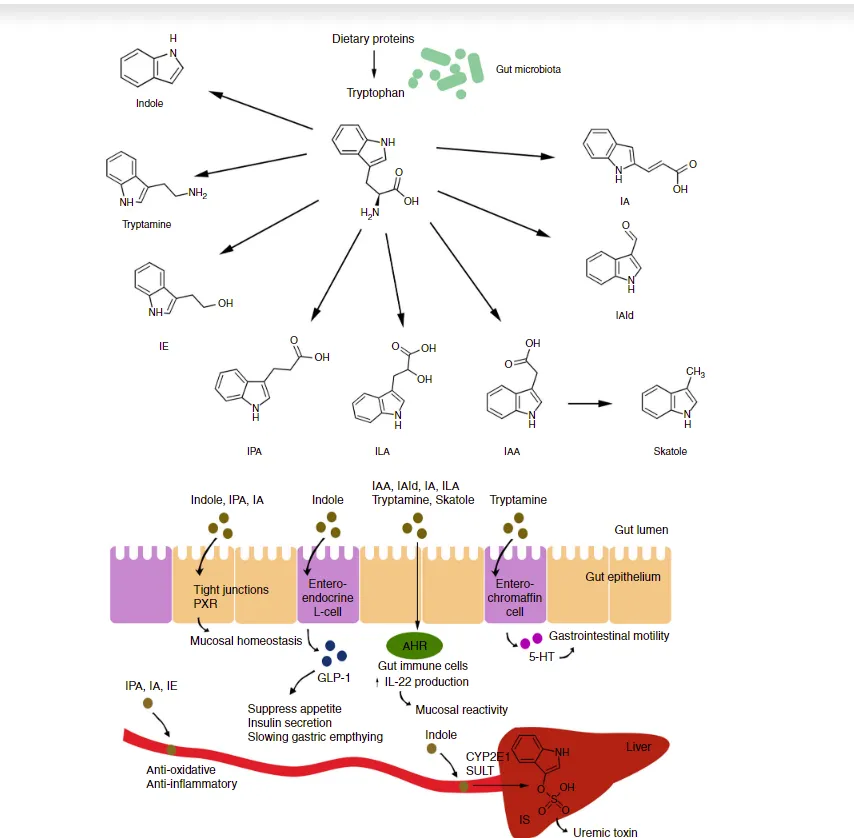

Odor from flatulence/belching usually comes from sulfur-containing compounds such as methanethiol, dimethyl sulfide, hydrogen sulfide, as well as short-chain fatty acids, skatoles, indoles, volatile amines, and ammonia.

When excessive intestinal gas does occur there may be several causes:

Consumption of rapidly fermentable foods and nonabsorbable foods like dietary fiber and resistant starches in to the diet. (more on this below)

Malabsorption disorder such as Sibo, Dysbiosis, Celiac Disease, Lactose intolerance, Fructose Intolerance.

Excessively high protein does due to the agonism of GLP-1 which slows motility

Insufficiencies in innate digestive function elements such as pancreatic enzymes , brush border enzymes, bile , and proper stomach and intestinal PH.

Excessive air swallowing such as from straw drinking, chewing gum, drinking carbonated beverages, gulping food and beverages, smoking, and mouth breathing. This is common in anxiety.

Migrating Motor Complex disruption which usually happens such as irregular eating patterns, binging, purging, and grazing.

Decreased gas absorption due to dysfunctional gas clearance because of motility disruption. Such as with diabetes, scleroderma, pseudo-obstruction, and from certain medications.

Decreased gas absorption to obstruction such as adhesion or intestinal or pelvic masses.

Infections such as Giardia, H. Pylori, or Clostridium difficile may cause excess gas.

Other more unusual causes are due expansion of gas due to changes in atmospheric pressure.

Dietary Factors

From: An overview of established relationships between dietary intake, key biological processes and VOC production. Adapted from Kurada el al. 2015

Hydrogen: Ingested carbohydrate and protein are sources for H2 production. In healthy individuals, certain foods with high concentrations of oligosaccharides, such as stachyose and raffinose found in legumes, or resistant starches (flours made from wheat, oats, potatoes, and corn), cannot be completely digested by enzymes within the normal small bowel, leading to increased H2 production by resident microbes.

Hydrogen sulfide gas production has been linked to foods rich in dietary amino acids (cysteine, taurine, methionine). Foods rich in cysteine, taurine, methionine rich foods consist of Beef, Eggs, , Poultry, Soy/Tofu , Pork, Lamb, Fish, Shrimp Tuna Salmon ,Mollusks, Saturated Fats, and a few plant products like white beans, and Quinoa.(1)

Methane production by dietary factors is unclear , however some link has been shown to fat consumption and/or due to fecal bile content. Meaning Methane production seems to go down if there is adequate bile acid excretion in the colon. The presence of bile seems to lower methane production . Since there are many dietary and functional factors that regulate bile production this area is quite complicated. There is much to learn. 95% of Bile is normally reabsorbed in the last part of the small intestine and the remaining 2-5% is sent to the colon for excretion. So right now we may assume if there are low amounts of the colonic bile then methane gas is more likely to be produced. (2)

Microbial Production of Gas

In the gut , CO2 is generated from digestion of fat and proteins in the upper gastrointestinal tract, also from bacterial fermentation from the digestive soup (intraluminal digestive material) , or may be liberated from the interaction of acid and bicarbonate . CO2 is mostly absorbed in the by the body and absorbed before it reaches the colon. However if present in the flatulence it is probably due to bacterial fermentation in the colon. If CO2 flatulence is excessive it may be due increased Non-digestible fiber making its way to the colon.

Hydrogen H2 is both produced and consumed by our gut microbes. In fact two subtypes of microbes are termed hydrogen gas consumers. One being the Methanogens from the Kingdom Archaea which consume four molecules of Hydrogen to produce 1 molecule of Methane. The other are the hydrogen sulfide producing organisms such as Desulfovibrio piger which consume 2 molecules of Hydrogen to produce 1 molecule of Hydrogen sulfide. Also acetate (a short chain fatty acid is produced via consumption of hydrogen). Microbial producers of hydrogen are vast.

Hydrogen Sulfide producers include:

Desulfovibrio spp.

Salmonella spp.

Campylobacter jejuni

Citrobacter freundii

Aeromonas spp.

Morganella spp.

Proteus spp.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Yersinia enterocolitica

Hydrogen Producers include:

Streptococcus: primary colonizers of the human oral cavity

Escherichia coli: primary in the lower intestine

Staphylococcus species: primary colonizers of the upper respiratory tract and on the skin

Micrococcus: primary colonizers of the oral cavities, mucous membranes, and skin

Bacteroides: most abundant phylum of the GI tract

Clostridium: primary colonizers of the intestinal tract, playing a crucial role in gut homeostasis by interacting with the other resident microbe populations.

Peptostreptococcus: normal inhabitant of the healthy female reproductive tract, normal flora of the mouth, upper respiratory tract, intestinal tract and skin

Enterococcus species: primary colonizers of the gastrointestinal tract.

Methane is thought to be produced primarily by Methanobrevibacter smithii

How often should you have flatulence? The frequency of flatus released varies between 10 and 20 times per day in healthy subjects . However, the complaint most common is the odor of the gas out of fear of embarrassment.. But often times complain because the gas production has been extremely uncomfortable, unpleasant, and is limiting desire to eat and or socialize. The odorous aspect of flatulence is largely due to sulfur-containing compounds, such as methanethiol, dimethyl sulfide, and hydrogen sulfide, as well as short-chain fatty acids, skatoles, indoles, volatile amines, and ammonia. Hydrogen sulfide has a particular egg like odor . Ammonia production be from excessive putrefaction of protein in the gut. Skatoles and indoles are usually a result of bacterial dysbiosis or overgrowth.

What to do if you have you feel that gas/flatulence is a problem in your health? It is important to have an exam and discuss all the reasons with your primary care provider; if you feel you want additional advice then discuss with a functional medicine or naturopathic physician that specializes in GI health or discuss with a comprehensive gastroenterologist. There are tests like the Lactulose Hydrogen/Methane/Hydrogen sulfide test such as Trio Smart. Also VOC testing will soon be available as a biomarker.

Stool and digestive testing can also help with understanding imbalances. Its also important to bring up any red flags such as nighttime symptoms, pain, unexplained weight loss , blood in stool, vomiting, and severe constipation.

If you are interested in more information please check out my recent interview with Mark Pimentel, MD on SIBO and IBS.

sources:

Martha H Stipanuk, Metabolism of Sulfur-Containing Amino Acids: How the Body Copes with Excess Methionine, Cysteine, and Sulfide, The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 150, Issue Supplement_1, October 2020, Pages 2494S–2505S, https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxaa094

Florin TH, Woods HJ. Inhibition of methanogenesis by human bile. Gut. 1995 Sep;37(3):418-21. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.3.418. PMID: 7590441; PMCID: PMC1382826.

Van Malderen K, De Winter BY, De Man JG, De Schepper HU, Lamote K. Volatomics in inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. EBioMedicine. 2020 Apr;54:102725. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102725. Epub 2020 Apr 21. PMID: 32330874; PMCID: PMC7177032.